Wassily Kandinsky

Discover Kandinsky’s Vision

Kandinsky saw art as a language built from lines, colors and inner vibration.His work charts the path from visible reality to pure abstraction — a foundation that shaped Bauhaus thinking and continues to influence design today.

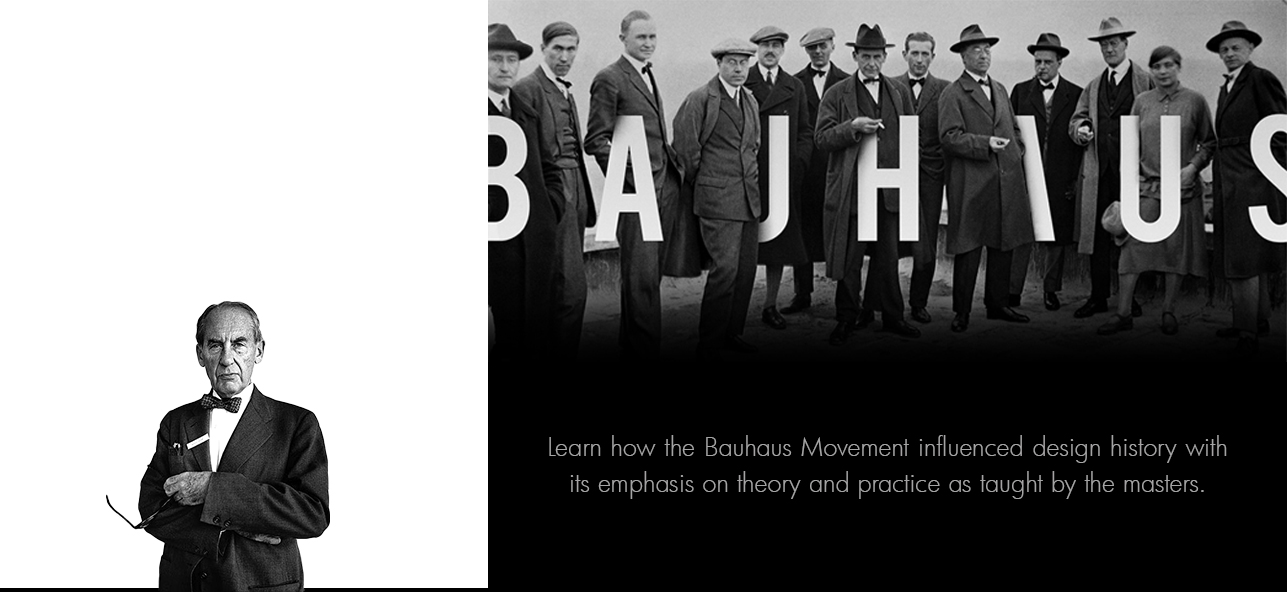

Bauhaus Movement · Editorial perspective

The Soul of Bauhaus Design

For Wassily Kandinsky, the Bauhaus was more than a school for form and function. It was a place where color, geometry and inner experience could be tested in real space. His vision shaped not only abstract painting but the way we read architecture, textiles and objects in Weimar and Dessau today.

Wassily Kandinsky at the Bauhaus

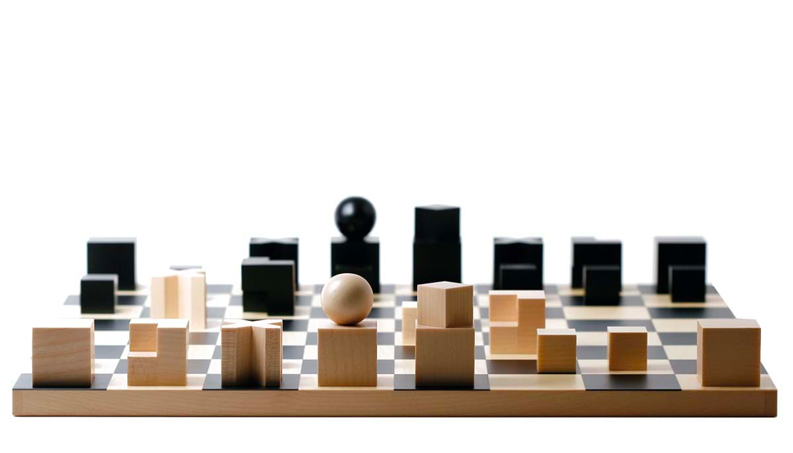

When Kandinsky joined the Bauhaus in Weimar in 1922 and later moved with the school to Dessau, he brought something radically new into the workshops. Instead of starting with style, he started with perception. Students analysed points, lines and planes before they ever designed a chair or a façade. Geometry became a language that could be read and composed.

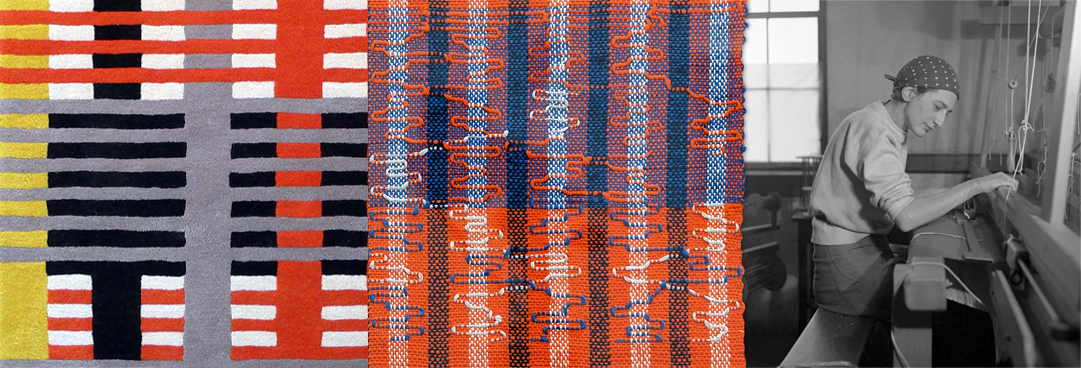

In his teaching at the Bauhaus, Kandinsky connected three key fields: painting, architecture and craft. Seminar rooms and studios in Dessau became laboratories where circles, triangles and squares were not decoration but tools. A red triangle, a blue circle and a yellow square could already suggest tension, calm or balance, long before a motif appeared.

Color, form and the inner necessity

Kandinsky’s book Concerning the Spiritual in Art was written before the Bauhaus, but its ideas found a concrete home in Weimar and Dessau. He spoke of an “inner necessity” that should guide every artistic decision. At the Bauhaus this turned into a shared method for painters, weavers and architects.

- Color was understood as vibration, capable of moving the viewer inwardly.

- Form provided structure, giving these vibrations a clear framework in space.

- Composition created rhythm, directing how the eye travels across a canvas, a carpet or a glass façade.

“Color is a power which directly influences the soul.” — Wassily Kandinsky

This way of thinking changed everyday design. A woven border, a tiled floor or a window rhythm could be “read” like a painting. Modernism in Dessau is therefore not only white walls and flat roofs. It is a precise choreography of color and form, calibrated to how we feel and move in a space.

From canvas to classroom to city

What Kandinsky developed in his paintings became curriculum in the Bauhaus classrooms and finally visible in the city. In Dessau, you can experience this translation step by step: the analytical drawings in teaching materials, the colored planes in the Bauhaus Building and the carefully set accents in the Masters’ Houses.

Instead of separating fine art and design, Kandinsky helped to connect them. A carpet pattern, a staircase wall or a studio window could all be part of one visual sentence. This is why the Bauhaus is still referenced when contemporary designers speak about visual identity, wayfinding systems or immersive architecture.

Why Kandinsky still matters for Bauhaus lovers

For many visitors, the first contact with Bauhaus is a famous lamp, a tubular steel chair or a black-and-white photograph of the Bauhaus Dessau façade. Kandinsky invites us to look one layer deeper. He asks: What does this composition do to you as you stand in front of it. How does the alignment of windows, the contrast of colors or the weight of a line change your state of mind.

Seen this way, Bauhaus design is not only functional. It is emotional and precise at the same time. This is the “soul” in Bauhaus design — not something mystical, but the result of carefully tuned relationships between color, form and human perception.

Watch: Bauhaus color, sound and abstraction

Connecting to your own Bauhaus journey

Whether you encounter Kandinsky on a museum wall, in a book or through a guided visit in Dessau, the underlying questions remain the same. How do colors interact. Where does tension arise. Where does the composition come to rest. Once you start seeing with this Bauhaus-trained eye, carpets, posters, buildings and digital interfaces reveal their hidden structure.

The Soul of Bauhaus Design is therefore not a single object or painting. It is a way of looking at the world that began in places like the Bauhaus studios in Weimar and Dessau and continues in today’s design practice. Kandinsky’s legacy lives on wherever form and color are used with clarity, care and inner necessity.

Wassily Kandinsky Composition VIII Rug

Wassily Kandinsky Composition X Rug

Wassily Kandinsky Gloomy Situation Rug

Wassily Kandinsky Surfaces Meeting Rug

Wassily Kandinsky Art

Wassily Kandinsky Circles in a Circle 1923

Wassily Kandinsky Composition 1944 Rug

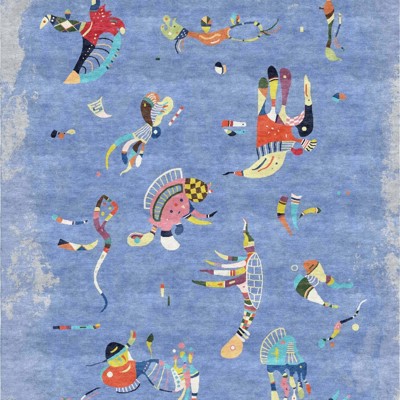

Wassily Kandinsky Sky Blue Rug

Anni & Josef Albers

Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Houses

Breuer's Bohemia

Ezra Stoller

Modern Architecture Since 1900

Walter Gropius - An Illustrated Biography

New Bauhaus Chicago - Experiment Photography

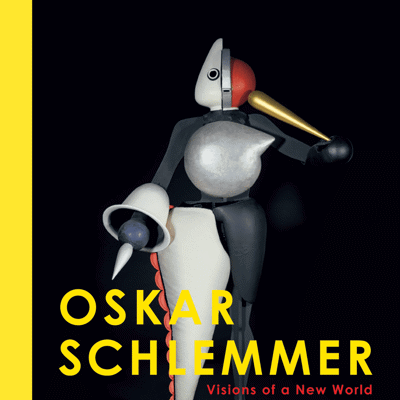

Oskar Schlemmer - Visions of a New World

Paul Klee - Landscapes

The Whole World a Bauhaus

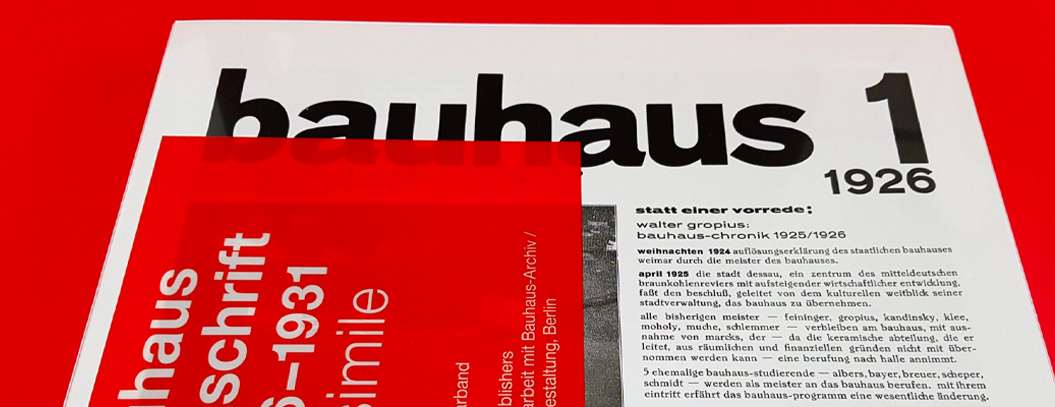

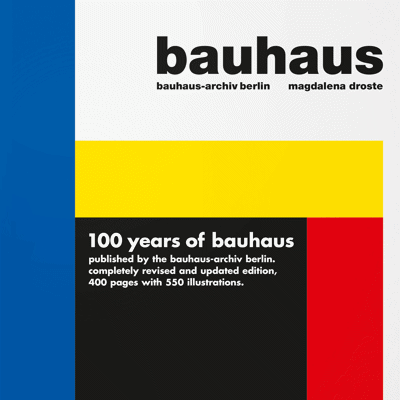

100 years of bauhaus

State Bauhaus in Weimar 1919-1923

Wassily Kandinsky Journey

Kandinsky’s vision shaped the language of color and abstraction. With Bauhaus Experience, you can explore Weimar and Dessau where his ideas grew, evolved and reshaped modern art.